Bartholomäus Schnell. Roughneck, „free artist“ and Pioneer of Letterpress Printing in VorarlbergAn exhibition of the Vorarlberger Landesbibliothek in the Jewish Museum Hohenems

The establishment of Vorarlberg’s first printing house by Bartholomäus Schnell in 1616 and the settlement of Jews by Count Caspar of Hohenems starting in 1617 are closely linked not just in time. With the printing house, the Count brought an important means of propaganda, legitimacy, and education to his small realm, which enabled him to write history autonomously. By having the Emser Chronik (Ems chronicle) printed, the Count created for himself and his rule a dignified past and, at the same time, substantiated his political ambitions; by settling Jews, he continued his policy of developing Hohenems to become a town and opened up new economic possibilities to “elevate the market” through commercial relations, capital, and tax revenues.

The planned printing of a Hebrew prayer book by Bartholomäus Schnell denoted the possibility of a close relationship between the Hohenems printing house and the economic and social ambitions of the Jewish community.

Finally, both the histories of book printing as well as, most notably, of the Jewish community found in Aron Tänzer their first serious historian and archivist—albeit at a point in time when the comital rule had long been over and also the Jewish community in decline.

The exhibitions on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Vorarlberg State Library and of Aron Tänzer’s book “Die Geschichte der Juden in Hohenems” (the history of the Jews in Hohenems), simultaneously present two mavericks who could hardly be more different.

Vorarlberg’s history of letterpress printing begins with Bartholomäus Schnell the Elder of Langenargen on Lake Constance. He had learned the “free art of letterpress printing“ at the Abbey of Saint Gall and began to operate a printing house, the first in today’s Vorarlberg, in the County of Hohenems in 1616. Already with his first work, Emser Chronik, Schnell succeeded in creating a “masterpiece in the art of letterpress printing” that was described as “the most beautiful book ever printed in Vorarlberg”—not least by Rabbi Tänzer, who in 1900 dedicated his first essay to Schnell and the cradle of Vorarlberg letterpress printing. Further 62 works of print are known; probably, however, these constitute just a small part of the entire output. Schnell worked in Hohenems for over thirty years not only as printer but also as binder and seller of books. While Schnell was a loyal subject of the count, he was also an embarrassing one who repeatedly engaged in verbal abuse and acts of violence and frequently got into trouble with the law. He was not averse to drinking one too many either. Schnell would often spend days and nights in the Ems jail. Nevertheless, he felt deep connected with the comital market town, and also the count appreciated the printer’s work. Probably in early 1649, certainly before April 19, Bartholomäus Schnell passed away.

Several renters, among them also his son Bartholomäus Schnell the Younger, continued the business until it was shut down for several years in 1680 and for good in 1730.

With this exhibition, based on an initiative by Erik Weltsch, and the accompanying publication, the Vorarlberg State Library—in the framework of its 100th anniversary— wishes to convey to a broader public the history of early letterpress printing in Vorarlberg. Knowledge of this topic has significantly increased through the discovery of numerous records and works of print. A younger audience is addressed as well by providing insights into the craft of book printing and binding.

Aron Tänzer.Rabbi, Researcher, Collector and Loving PedantAn exhibition of the Jewish Museums Hohenems

Aron Tänzer’s book Die Geschichte der Juden in Hohenems und im übrigen Vorarlberg (History of the Jews in Hohenems and all of Vorarlberg) celebrates its 100th anniversary this year. To a large extent, the permanent exhibition of the Jewish Museum Hohenems is based on knowledge provided in this book. Hence, this is also an occasion to trace the life story of its author. The exhibition “Aron Tänzer. Rabbi, researcher, collector, and loving pedant” wants to provoke interest in a biography filled with contradictions. Here, the Jewish Museum ponders, as it were, its own foundations. Most of our knowledge of the early history of Hohenems and Vorarlberg is owed to Aron Tänzer’s search for order—in his life and in history. Admittedly, a knowledge that is steeped in many a wish, hope, and false certainty.

Tänzer’s story is a story of burgeoning reason, his world is a world of restrained urges, his authorities are legitimate rule, and the German-Jewish relationship is a backbone of progress. Thus, to him the past presents itself as a prologue to a German-Jewish symbiosis, which would turn out to be an illusion already during his lifetime—and to a universal Jewish ethics, which permeated neither the Jewish life Tänzer described nor even his own.

Aron Tänzer, born in Bratislava in 1871, was a graduate of the renowned Bratislava yeshiva. He went on to study philosophy, German language and literature, and Semitic philology in Berlin and Bern. Together with his young wife, Rosa, Dr. Tänzer moved to Hohenems where he assumed the vacant rabbi’s position in 1896. The creation of order, the collection and passing on of knowledge informed Tänzer’s life and work.

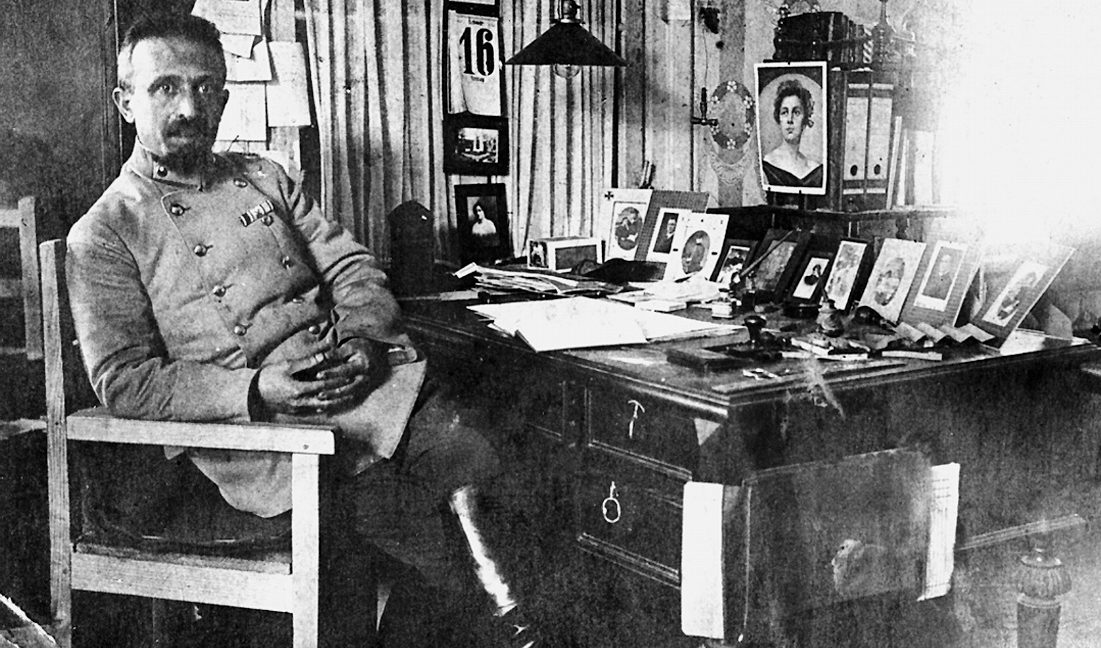

In Hohenems, these characteristics found their expression particularly in the above-mentioned book on the Jewish community and in the creation of order in the archive. Tänzer’s handwritten archival register, which is kept and presented in the Jewish Museum Hohenems, constitutes the basis for today’s Hohenems municipal archive. Besides his work as rabbi, Tänzer was consistently interested in publications dealing with historical, religious, and social-political issues and especially in lectures on the most varied, mainly literary topics. A treasure that allows us today to obtain further insights into the world of this versatile rabbi are his surviving diaries and letters, in which he tells about his work, but also in a loving, pedantic manner about his children, especially their ethical and professional development. Following a brief intermezzo as rabbi in Merano, Aron Tänzer assumed the rabbi’s position in Göppingen in 1907. Again, those thirty years in Göppingen were filled with Tänzer’s historical, literary, and theological research and publication activities. His reputation as an outstanding lecturer reached far beyond Göppingen. As a convinced patriot, Tänzer left his family and community to volunteer during World War I as a Jewish chaplain in the German Army. His notion of a German “Kultur-Nation” was shattered in the face of an anti-Semitism that became ever more socially acceptable in Germany. His will reads like a dementi. Shortly before his death, Tänzer noted appalled: “No German eulogy whatsoever shall be held at my funeral, only the customary Hebrew prayers.” Dr. Aron Tänzer passed away on February 26, 1937.

Concept Schnell:

Kerstin Ebenau and Norbert Schnetzer (Bregenz)

Concept Tänzer:

Eva-Maria Hesche, Patrick Gleffe and Hanno Loewy (Hohenems)

Design:

stecher id (Götzis)

Roland Stecher und Thomas Matt

Museum education:

Helmut Schlatter (Hohenems)

Kerstin Ebenau (Bregenz)

Secretary:

Renate Kleiser